I found my old smartphone yesterday, digging through my nightstand. An old Pixel 5a. It took a bit of sifting through my records, but I think I bought it at the end of 2021. It’s almost fifteen years old.

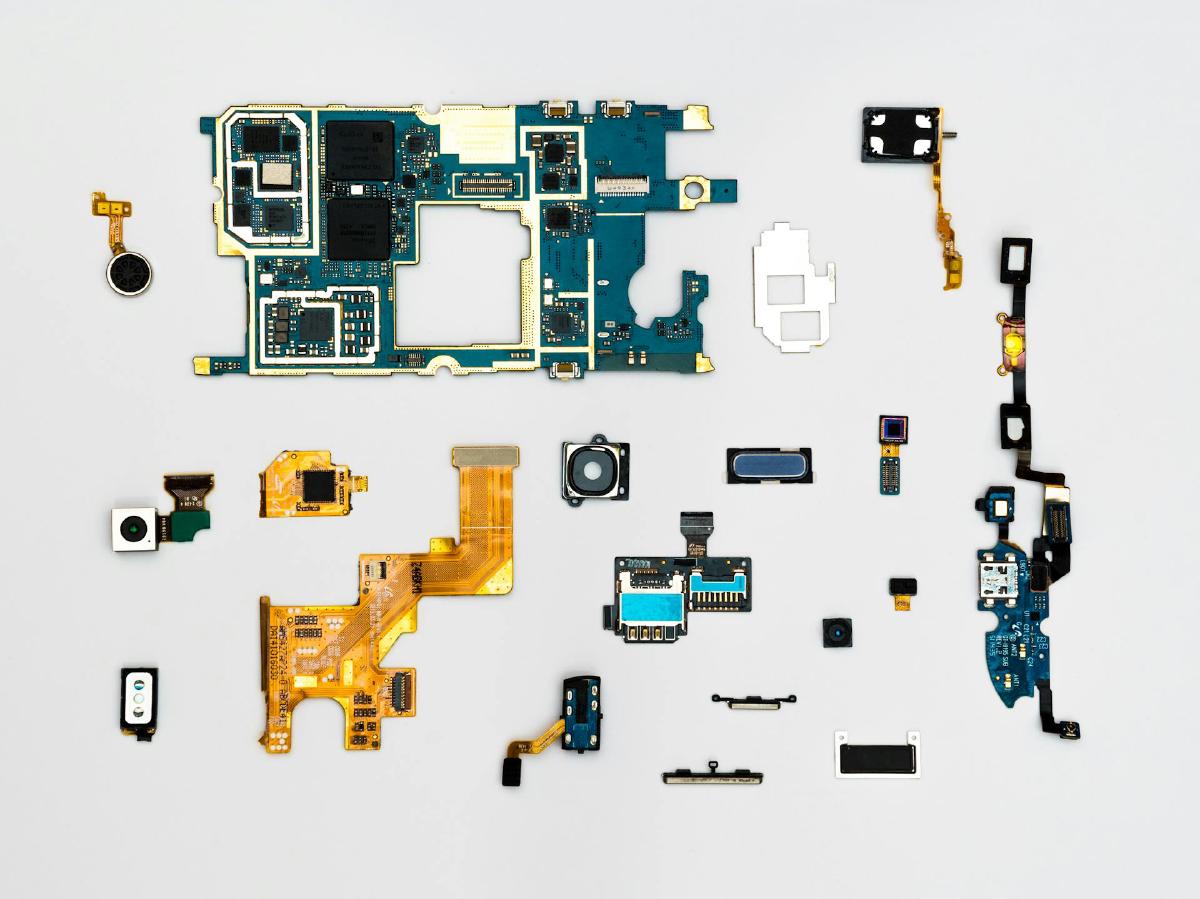

My curiosity made me want to immediately boot it up and check it out like a digital time capsule, but the old lithium-ion battery had swollen, and I know better than to screw around with running power through a puffy battery. Of course, this was a 2020s device, which meant it wasn’t designed to be easily fixed. The battery wasn’t accessible or swappable, at least without some effort.

I take it for granted now, but I remember how thrilled I was when we got comprehensive, meaningful Right to Repair laws passed. As a 90s kid, I just barely recalled the Radio Shack era of standard components and devices you could tinker with yourself, but I realized, as I hopped on my bike with the offending phone in my pocket, that it was only after Right to Repair that the Goblin ever got to see things like that. For me, it felt like a homecoming—for her, it was a brand new shape to the world.

Days before the Goblin was born, when R and I were both off work and anxiously awaiting the first signs of labor, I dropped this phone smack on the ground, and the screen utterly died. The nearest repair center was an hour north. Right to Repair made replacement components standardized, accessible, and affordable, and lowered the skill barrier required to fix your stuff without bricking it. Fixing devices got closer to repairing a bike than defusing a bomb, and that meant more people were able to set up shop doing that for the community.

Today, I got to ride 10 minutes on my bike to the fixit instead of spending two hours there-and-back on the highway.

Of course, once I pulled into the shop, I realized my mistake. I’d been so excited to peer into the past on the Pixel that I’d overlooked the obvious thing: it was a pre-RtR phone. And sure enough, the fixit wasn’t able to do a direct battery swap; she just didn’t have a battery with the exact right dimensions. She did, however, pull the swollen battery out, so I could safely power the thing on if it was connected to AC. That was good enough for today, and honestly for the best. I’m not as cavalier about the batteries stuffed full of rare earth minerals as I was in my 20s and 30s. Today’s little curiosity project is not worth the extraction.

Because the phone had been sitting, untouched, in a drawer for something like a decade, all of the apps had been preserved in their ancient state. A decade of software updates had bypassed the Pixel, so I could see what phones and apps used to look like. To be sure, many of them pinged home to servers that no longer existed. One meditation app got stuck on the login screen, presumably trying to log in to computers that had long since been spun down. It was a bit like walking through the ruins of an abandoned building, simultaneously witnessing what remained and being mindful of the holes in the floor.

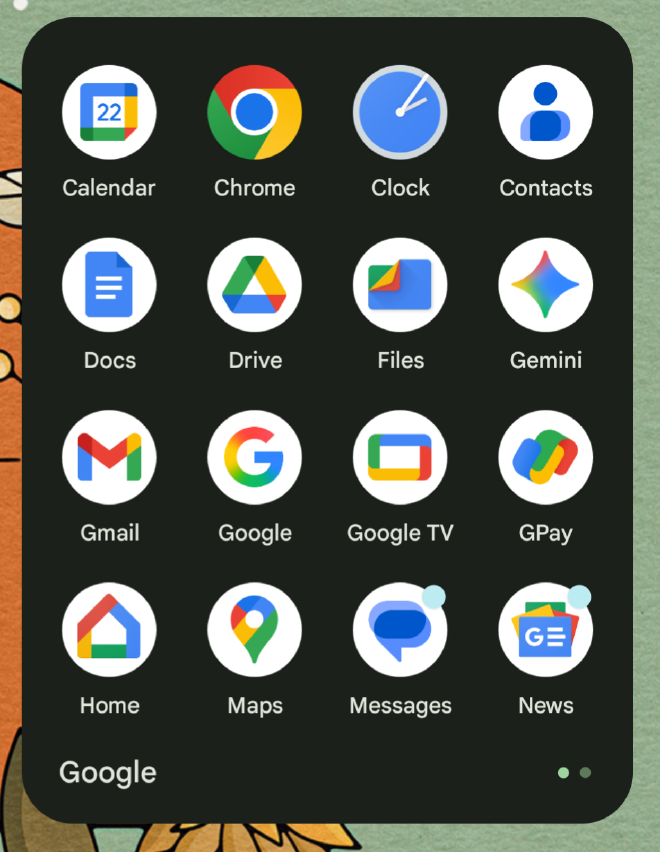

The first big wave hit me when I found a folder of apps I’d just labeled “Google”. It had 21 different icons in it. That’s so many, the folder had to have two separate sections.

Now, back in the mid-2020’s, I was hardly ignorant of the extent of Google’s data collection. I have long been a crotchety curmudgeon about surveillance tech. But this was before the Jefferson Park Elementary profiling scandal, and before the Palantir Terrors. Before everyday people, not just tech curmudgeons, grasped what it meant to be surveilled and profiled. In 2025, we were just on the cusp of the Digital Sovereignty movement taking off, so even neo-Luddites like me were often still defaulting to Big Tech’s centralized products.

I look at those 21 icons and shudder to think about how much data was being beamed back to Google for them to profile me with.

My alarm clock told them when I usually woke up, and how long a timer I usually set for naps. Calendar gave them every event that was important to me. Through Contacts, they knew who I wanted to stay connected to, and how to reach them (a trove of data that we now know was mined extensively by the Trump regime to build dissident maps during the Terrors). Docs contained drafts of my writing. Maps tracked everywhere I ever went. Gmail told them not only who I interacted with, what I was subscribed to, and what I bought, but also what sorts of messages got my attention, and when.

I’ll be honest, it felt like looking at a set of marionette strings, carefully folded up in their box, and I backed out of that folder pretty quickly. I was glad the Android phone couldn’t connect to WiFi, because I was sure it would ping some Google server somewhere. Even now, with Google significantly beaten back from where it was in the 2020’s, that felt too much like Pippin awakening the Balrog.

Back in the 2020’s, Google and the other Big Tech companies felt like unstoppable titans. They moved with inevitability. And so, now, when I think about what we managed to plant in their footsteps, it makes me smile.

Digital Sovereignty really started rumbling in 2025, when US tech companies under the Trump regime wouldn’t guarantee their international customers that their private data was protected from the US government’s prying eyes. I don’t remember exactly who started it—France, maybe?—but this tipped a domino. Governments started realizing that data centralization in the hands of massive private corporations was a liability, and as they funded and promoted more open-source alternatives, we saw a flourishing pushback against the convenience of Big Tech’s clouds.

Closer to home, after hemming and hawing about it for a while, a group of us finally started a little co-op, and began running a suite of apps for anyone in our community who wanted them. We started with alternatives to some of the big ones, like email, photo storage, calendars, and contacts. As more people signed up, we were able to add additional things, like a humane social network, a social reading site, a simple blogging platform, and an events scheduler. We have weekly workshops to help people understand the tech they’re using.

I’ll be honest, I didn’t think people were going to be interested at first, and sure enough, it took a little bit to get off the ground. But the shift came, gradually, often spurred along by our workshops. I can still remember the stunned look some people got when they learned just how much data Big Tech had on them, and how eager they were to switch.

Today, I don’t use my phone nearly as much as I did in 2025, back when I was on that Pixel. That was another side effect of disconnecting from Big Tech’s apps. When my “engagement” was no longer being monetized, the phone returned to how I remembered it being in the early days of smartphones: a useful tool, not an addiction device. We’re still working on it—the work is never done—but it sure feels like we’re getting closer to tech that serves us, not the other way ‘round.

More Reading (for the present) #

- Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention—and How to Think Deeply Again, by Johann Hari

- The Future is NOT Self-Hosted, by Drew Lyton

- Tucson Mesh on Community-Run Internet, on the Live Like the World is Dying podcast

- World Without Mind: The Existential Threat of Big Tech, by Franklin Foer